Germain Louvet, danseur étoile.

You started dancing at the tender age of seven at the Conservatoire à rayonnement régional de Chalon-sur-Saône which is almost a caricature of bourgeois life in a way. Were your parents hoping to turn you into the ultimate archetype of proper manners?

Well, not really, because I started dancing at my village’s tiny jazz dance school at four years old. My introduction to dance was more of the day-care variety, where you learn to move your body and tune into music. And, besides, I’m not from the type of family that tries to reproduce bourgeois codes at all, simply because it’s not a bourgeois family at all. So it was a bit out of the blue. When I asked to take up dance, my parents were just happy that I was doing something I liked, so they let go of any preconceptions and accepted that I could do it without any problem.

One supposes you took to it quite rapidly…

Yes, and that led me quite naturally to ballet. I didn’t even do it on purpose. My teacher at the little dance club told me: “If you want to go further, you should go to the conservatory.” So I learned ballet there, which became like a second language. That’s why, in my mind, it didn’t have anything to do with class. It was only later that I discovered that aspect of it.

Seeing as ballet is supposed to make young girls more graceful, doesn’t freezing it into this type of bolted-down elitist vision do disservice?

I think it’s very complicated to deconstruct because it has become self-surrounding. I’d rather reverse the problem and focus on people who feel that classical dance isn’t for them because they don’t come from a background where they were given the codes or education to understand dance. And therein lies the problem because you can’t reduce a hobby, and even more so an artistic practice, to a way of seeing society.

It reminds me of friends of mine who went to dance classes when they were little and, who in turn, enrolled their daughters. Nowadays, when they go to the opera, they expect the shows to serve up the imaginary world they built up as children…

There’s practicing dance, and then there’s going to see shows. The practice is very much influenced by the performances and the audiences who go to see them. The Opéra, whether lyric opera or ballet, is a place for the bourgeoisie and the aristocratic elite, which flourished under the Second Empire; the Palais Garnier dates from that period. But the story goes back even further, to the monarchy. So, even if there were operas that also appealed to the working classes, there was a bourgeois order that dictated the rules of what happened in an opera. As a result, the public stems from this history and has forged the aesthetics that characterize us as performers both in terms of selection methods and how we present a story or an interpretation. And so, classical dance, which emerged from the baroque – itself practically invented by Louis XIV – has this very aristocratic history of being produced by people who have mastered the art of being noble.

Currently, an institution like the Paris Opera is criticized for its cost, elitism, and irrelevancy in the face of an aging audience, save perhaps for a young, relatively middle-class contingent that was introduced to it early on.

And sometimes, they don’t go to the Opéra out of desire or passion but rather as if prompted by certain conventions. It can almost become a club. Of course, things have changed a lot over the last fifty years. I sometimes go to see shows, and I’ve noticed an evolution, no doubt resulting from initiatives to open up the Opéra to new audiences, like previews for young people, programs for school children, and such. There’s also an online interface that lets you watch shows from your computer. But it’s still a major challenge.

But is this not all a false problem, since it is, at its core, a form of entertainment desired and supported by the often bourgeois and sometimes conservative elite, who want to be served a show that’s just the way they like it? Wouldn’t that explain the controversies that arise with every attempt at modernization – for example, when Benjamin Millepied renamed the “Dance of the little Negroes” in La Bayadère to the “Dance of the Children” and wanted to put an end to the use of blackface.

Surprisingly, these are relatively recent controversies. What Millepied did, in my opinion, is not to modernize. It’s more a question of developing works aligned with the values that the Opéra wishes to convey. Indeed, it contributes to the accessibility of the works. Still, I believe it was something vital rather than a little cosmetic that would tend to “look more modern or democratic.” Besides, there are always those conservatives – who have been all the more vocal since those controversies started happening with greater frequency – who will say, “but why change things?” As far as ballet is concerned, it’s the scarecrow of cancel culture that has stimulated certain conservative forces who want to “freeze” something that’s impossible to freeze because it is dance and movement. It’s ephemeral, it’s alive and it’s dependent on the performers who are dancing at the moment and who won’t be the same in twenty years. And that’s interesting because the ballet tradition is one of oral transmission and perpetual evolution. Contrary to what you might think, we don’t perform anything the way it was first created. I’m talking in particular about the ballets like Swan Lake, La Bayadère, The Nutcracker, etc., which were created at the end of the 19th century. We have no tangible traces of what they were when they were created. Today’s productions of Swan Lake are the result of successive facsimiles, which lead to what we do today. So the argument that “we want to see Swan Lake as it has always been” is impossible to satisfy. We can’t dance Swan Lake today as we did 150 years ago. We’ve kept the same structure, but there have been additions over time, and we’ve forgotten that they were additions. And there are lots of other examples. For example, when Rudolf Nureyev took over the direction of the Opéra ballet, he wanted to do his own Swan Lake. At the time, the version being performed was by a choreographer named Vladimir Bourmeister, and in 1986, when Nureyev suggested creating a new Swan Lake, there was an uproar in the ballet, and the dancers went on strike because they didn’t want to change their version. So Nureyev had to accommodate everyone, and in the same season, he programmed Bourmeister’s Swan Lake and his own in parallel. Today, thirty-five years later, nobody remembers what Bourmeister’s Swan Lake was. The only Swan Lake that exists in Paris at the Opéra is Nureyev’s.

So it’s been thirty-five years and, we’ve once again set in stone something that would cause an outcry if it were to be touched…

There’s also the fact that we’re going to do something different every night. I never do exactly the same thing on stage. There are accidents that don’t necessarily show, which can lead to very beautiful things. So, nothing is ever set in stone. That’s why video – which has revolutionized ballet enormously, as it allows the creation of artifacts for transmission – remains tricky, because a video is a 2D version of a moment. So, if one night, I have a mini memory lapse and I do something differently, it’s captured on video and in ten years, there’ll be a guy who’ll want to learn Swan Lake and think it’s the original version the way the choreographer asked for, whereas at the time, I was just thinking about my grandmother. And the far-right people who were tweeting about changing certain parts get their due because they had no idea that the ballet is thirty years old, and that it was revived by Nureyev, who is Russian and not at all French.

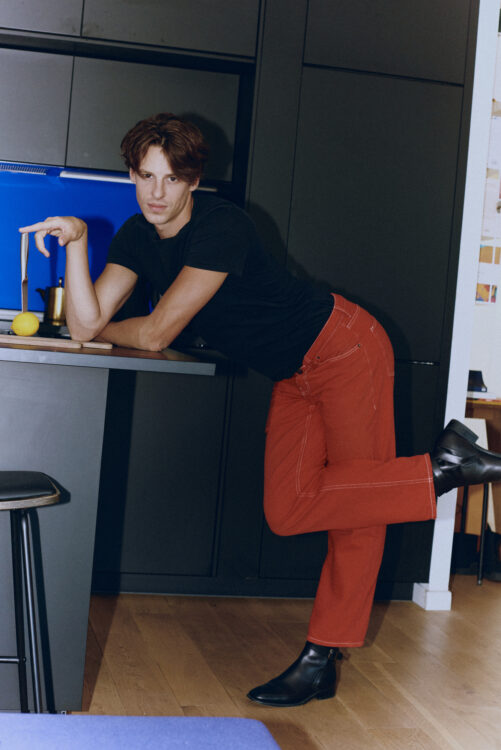

Do you ever feel that you’re an “element” that’s been selected and refined to match the canons and standards – waist size, arm length, shoulders – of a highly codified show, and that, in fact, it’s because you physically match these criteria that you’re part of it? In other words, do you ever feel that you’re an “ingredient?”

Yes, completely. Especially from the moment I was appointed danseur étoile, I had the opportunity to question how I got there, to look at my career path and question its rhythm. And without denying that I’m talented – or at least I hope so – and that I’ve worked hard to get here, some things have effectively polished me, and sculpted me to fit these criteria, these codes and this audience. On the other hand, I don’t find these things at all reductive for me. Of course, I’d like them to evolve, produce different aesthetics, and make way for more diversity. But it’s given me the freedom to express myself, to talk about it, to question the very mechanisms that got me here in the first place. There’s a fairly constant discourse on the part of successful artists about following your dreams at all costs, which I think is a pretty dangerous line of thinking because it gives the illusion that anything is possible, just like those magazines that only show unattainable houses or apartments. It just becomes a pipe dream, it means never questioning the system in which you’re working. I’m not saying that you should tell people “don’t have dreams in the first place,” but I do think it’s important to ask yourself what you want to put forward, and how. I know I fit these criteria, but on the other hand, I’m taking advantage of my position to talk about it, in the hope of changing things.

Isn’t a dancer’s body a design object, as defined by an institution, the Opéra?

I wouldn’t go that far because the greatest ballet artists I know from the last fifty years, on the contrary, are people who didn’t necessarily fit the criteria, the basic model, like Barychnikov. And Nureyev himself was rather short-legged and sort of stocky. Marie-Agnès Gillot is oversized by dancer standards. There’s also Agnès Letestu and plenty of other examples of great dancers who have inspired me a lot and turned their differences, which could have been seen as flaws, into essential qualities. On the other hand, I would never describe anyone’s body as an object, even a design object. I understand the question from a magazine that focuses on the aesthetics of non-living things, but I believe that the body is only the result of the will, the passion of the person who inhabits it. Besides, our bodies become interesting when they move. So design exists from the moment we set it in motion.

So a dancer is their own designer?

Yes, dancers are their own designers. To put it pragmatically, it’s up to us to decide whether we want to have a muscular physique, have long or short hair, etc. Each dancer shapes their own style, personality, and therefore reflects their own aesthetic to the audience, even if we have to wear costumes and so on.

That’s what interpretation is all about. When you have to work within a web of codes, it’s important to know how to play with them, to suggest something different. That’s where the artist emerges.

Yes, it’s quite fundamental, and that’s what I say to people who think that classical ballet is irrelevant. I feel much more freedom in classical ballet than in certain contemporary pieces where the choreographer is present. Some are extremely fussy, demanding right down to the placement of the little finger. In classical ballet, there’s a language; you know that the choreography is glissade grand jeté, but then, the way you do it is up to you. And even goes for the personality of the character you want to portray. In Romeo and Juliet, the character of Romeo, well, he’s written by Shakespeare, but once he’s transposed into ballet, you’re free to present your own version of Romeo.

It’s probably harder when the choreographer is there because he’ll conceive of the corps de ballet as an instrument.

In any case, he can make us go exactly where he wants. He can work with the dancer’s personality and interpretation, and thus involving him in his creation. But he also has the possibility – I know some very mechanical choreographers – of getting exactly the visual aspect he’s after. The fact is, we don’t have that kind of approach with classical ballets that are over 150 years old. In the corps de ballet, a little more so. When the thirty-two swans are supposed to be all the same, your personality is obviously a little more inhibited.

Classical ballet, as a body of work, is widely defined today.

Yes, classical ballet is a language, so it’s conceivable that one could create a classical ballet on a modern theme tomorrow. For example, my director did his version of Les Enfants du Paradis, where he created a ballet from scratch with the help of a composer based on Marcel Carné’s film. Then there’s Wayne McGregor, who’s more into a very expansive neoclassical form: he recently did Woolf Works, based on the work of Virginia Woolf, and he also did Dante Project, which takes Dante’s poem tableau by tableau.

Is this a way of evolving the language to include stories about relationships between characters that are a little less hetero-normative? Cinema has been no slouch in this area and is now broadening its horizons.

Undeniably, we’re a little behind the times when it comes to this. It’s both a demand from the public and a reflection on our part. If we faithfully transpose the material codes of classical ballet – Swan Lake, The Nutcracker, etc. – in favor of modern stories, well, in the end, it becomes a bit of a musical. If you take the codes of the show, with a narrative and exchanges, and put a modern story on top of them, it’s hard not to fall into the trap of entertainment. Because if classical ballets have lived for 150 years, it’s because they’re more than just entertainment. Behind it lies a certain form of universalism and also the invention of certain aesthetics. I’m not sure we need to go back to the classical ballet narrative system, with tableaux, costumes, acts and so on, while incorporating modern stories. We simply need to allow contemporary choreographers to tackle these subjects and use the classical vocabulary of pointes, pas de deux and adages in contemporary creations. People will always say that there are no classical ballets that tell modern stories, and that’s true. But at the same time, there are plenty of choreographers who do. For example, Benjamin Millepied did his version of Romeo and Juliet with his company at La Seine Musicale, and it’s a version in which the two protagonists, Romeo and Juliet, are sometimes danced by two women, the next day by a man and a woman, and the day after that by two men. It’s quite extraordinary to do that.

Are you also interested in contemporary ballet?

At the Paris Opéra, we have a repertoire that’s almost 50/50, so in the twelve years I’ve been there, I’ve had the opportunity to do contemporary pieces and work with contemporary choreographers. I’m interested in contemporary dance, but I’m not a frustrated classical dancer who wants to do contemporary. Some seasons are richer than others, and I did more when I wasn’t a soloist. I recently participated in Pina Bausch’s Kontakthof, Sasha Waltz’s Romeo and Juliet, and I worked with Carolyn Carlson. But I think it’s vital to continue to alternate. It feeds itself.

Ballet companies are usually housed in large institutions, in the heart of major urban areas, and cater to their need for entertainment and beauty. Is dance an urban art form?

Dance is an art form that takes the three dimensions of space and brings the body and movement as a fourth dimension into that space. In this way, it can become an urban art form, since in cities, it will be positioned in a highly regulated construction, inside theaters, and theaters have a place in the city, a function in the city and in society. But this art form can be positioned outside theaters, and that’s where it gets interesting, with spaces that aren’t designed for dance, but which take on meaning from the moment a dancing body takes to the stage within them.

Do you mean “urban” types of dance, where dance takes over the street?

The street becomes the theater for this type of dance, and I like to say that dance has no boundaries: The body that brings the theater where it is. From the moment a dancer starts dancing in the street, everything around him becomes the theater, and we become the audience. I’m thinking, for example, of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, which was not originally conceived by its architect, Dominique Perrault, as a stage space. I’ve heard that he’s very particular about the image rights of his buildings. Unluckily for him, it’s where most of the videos of people dancing, commercials and music videos are shot.

It is a giant podium of sorts.

The BnF is a good example: it has become a dance space and a theater. Dance doesn’t always have to be theatrical: it’s also a practice, whether solitary or collective, that can do just that.

Dancers seem to exist in a very protected environment in the heart of the city, the Opéra itself. Doesn’t it come as a shock when you leave for the outside world?

I think the idealized aim of what we’re doing is to bring what’s happening in the city to the stage. In Gisèle, when we talk about what’s happening in the village square, it’s potentially what’s happening in the Place de la République. It’s the same thing when two people meet and interact, as when Mercutio fights Tybalt in Verona’s market square. The emphasis is on things that happen in space. When I dance at the Opéra Bastille, the stage level is one floor above the street. And the dressing rooms overlook the street, practically the Place de la Bastille. They’re very close to passers-by and cars. The funny thing is that there are no walls, just swinging doors between the stage and a huge glass roof that spans the eight stories of the building overlooking the street. Under the glass roof, there’s a sort of square with a fountain. So we often go from the stage to this water fountain. There’s a disruption, the friction of the moment when you’re in costume, and you’re all sweaty, your head is full of what’s going on on stage – Tchaikovsky, Prokofiev, whatever – and you go fill your bottle. You look outside at people taking the Métro, living their lives, and if they turn their head, they see a guy in tights, disguised, made up. But often, they don’t even look because they’re mired in their routine, and it’s kind of fun to have these little moments of shock, and that’s what makes this theater interesting because it’s at the heart of this whole movement. It’s more difficult for the Garnier Opera House because there are more filters.

And then, after the show, you hop on your bike and ride home through the city, just like the passers-by you were watching from the fountain.

It’s worth pointing out because I always feel weird when I get on the subway after the ballet and find myself sitting opposite people who’ve just seen the piece and don’t recognize me holding the program in their hands. After all, I’m no longer in costume or make-up. It’s such a unique context.

It’s as if the vestals had escaped from the temple to hit the town!

Yes – that inaccessible, exceptional side is left behind inside the theater. Unlike much more famous actors or actresses, we have a physical daily routine where we go to our place of work, which is always the same, and then go home. We’re not in different locations all the time, or on a year-long world tour where we’re sent drivers to take us to the set or to catch our flights. But people always ask me where we all sleep together in the Opéra as if we were in boarding school. I ask them if they sleep with their team in their office and explain that I’m thirty years old and a professional like any other.

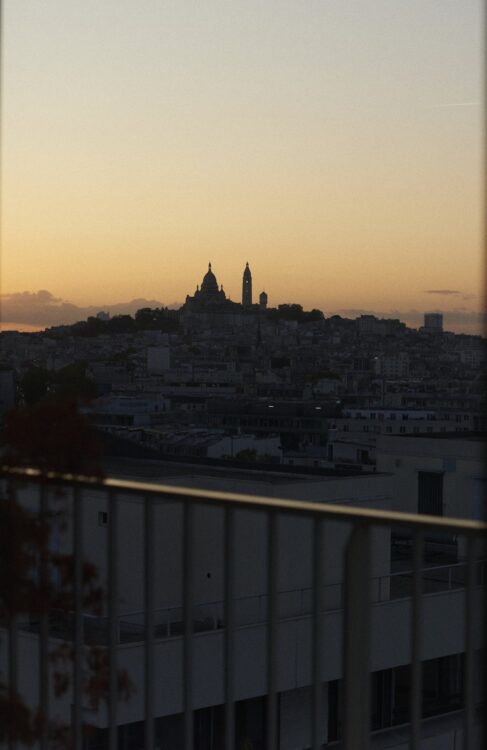

Is the city a source of energy and even inspiration for you? Or perhaps first and foremost a source of liberation?

I was born in the countryside, with a very rich relationship with nature, where you don’t need to take a car or a bike to go for a walk. At first, I had to get used to the city. It wasn’t easy, as I often felt the need to get away from it all on weekends. But yes, it became a source of inspiration, because I discovered the diversity of lifestyles, cultures, people with different social and educational backgrounds, religions, origins, objectives… And in my village, it was much less obvious. I don’t remember seeing any black children or children of the Jewish faith, for example. I come from a Catholic background, as did all my classmates, so I didn’t have access to this diversity. It’s fascinating to see how I had to wait until I was in my twenties to understand that there are people who have no references in common with me, apart from the city, this shared space. On top of that, Paris is this “cultural city” unlike any other in the world, and that even gets a bit stressful because you always feel like you’re missing something. The Opéra is not under a bell jar in relation to everything that exists and is emerging.

Does this city-as-stage present choreographies that speak to you? Can you describe them for us?

There are shows I’ve seen that have made me look at the city differently, that have made me see dance as boundary-less, existing outside of the dancing body, coming to life in the eye of the beholder. I’ve seen shows that reproduce what happens in the street. People walking, running, talking, their gestures, their habits. Even if Pina Bausch emerged in the 70s, she often stages her pieces in the 30s because what interests her is what happened in her home country to lead to the Shoah. She takes people and makes them do everyday actions. And she makes them repeat these actions, more and more aggressively, more and more hilariously, and by isolating them in this way, she allows us a glimpse, through this repetition, into just how much beauty and poetry they can conceal. There are choreographers like Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker who take a very scientific approach to the body, to movement, to its rhythm, to its “pendular” aspect, to the body as it walks, as it moves forward. If you make one person walk faster than the next, you create a sequence, a unison, as in music. This mirroring isn’t necessarily conscious or deliberate but exists because it cannot be avoided.

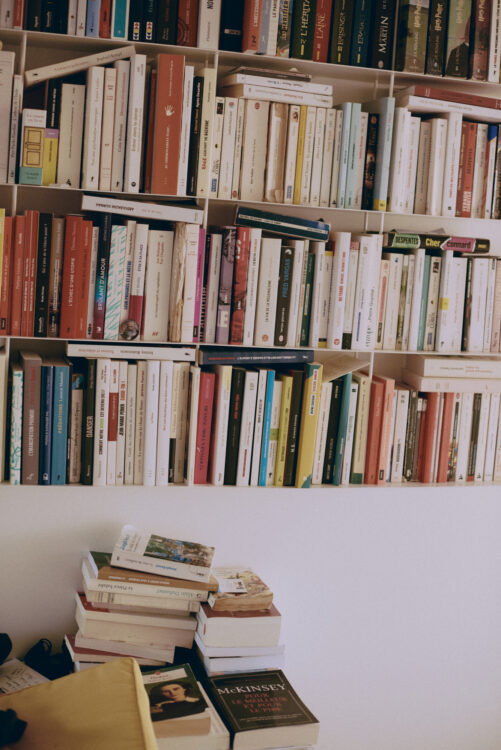

You’ve worked with Agnès B., and Jean-Paul Gaultier, so you must be interested in fashion. But also – and this is why we met – in architecture and design. Does this stem from being exposed to the costumes and sets of the stage?

In terms of fashion, I would say yes, because clothing is the continuity of the body. Clothes accentuate or give movement an even more realistic form than the body. There’s also the fame factor: after a while, people contact you because your danseur étoile status enhances the value of their clothes if you wear them. As far as design goes, it’s perhaps for more personal and familial reasons that I became interested in it. I’ve always had a fairly dilettantish interest in architecture – I’ve always been interested in spaces, how you play with light, the interplay between indoors and outdoors, how you fill spaces… And it turns out that I met a man, whom I’ve now been with for seven years, whose parents and sister are architects. This allowed me, through their eyes and their approach to the city – they do a lot of work on the rehabilitation of social housing – to refine my own vision of how to occupy a dwelling, how to make it more egalitarian, more pleasant.

Did you draw inspiration from your in-laws when building the apartment you share with your partner, Pablo?

Yes, and they were in turn inspired by things they’ve seen here and liked. A dialogue has developed between us around design. For example, our industrial-inspired radiators were an idea of Pablo’s parents. I gave them the Nessino lamp because they told me they loved it. The Klein blue of the credenza – they have a blue sofa – is one of my undying favorites. I put it in front of the cooktop, which is crazy because it’s a very fragile shade. They gave us the Airborne chairs because they had too many. I bought the little yellow garden furniture because I wanted it to complement the credenza – then they bought garden furniture in exactly the same color, so it’s getting a bit funny.

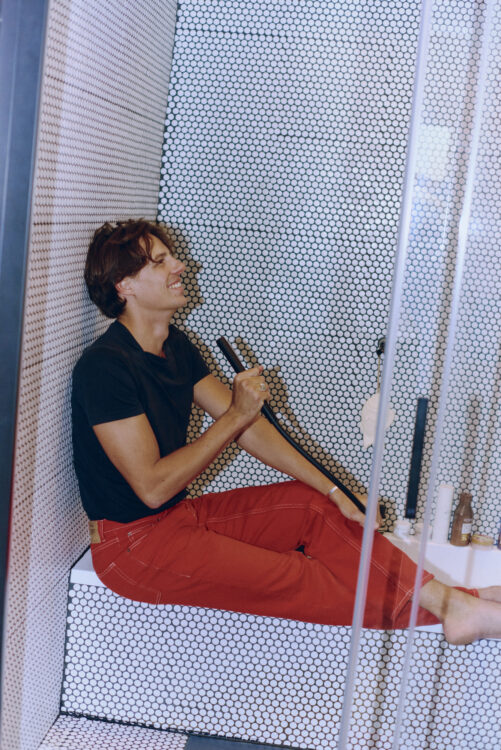

Can you tell us about the place where you live? What role does it play in your life?

I feel at home here. It’s a refuge. I travel a lot when touring abroad. This specific apartment has replaced my constant drive to escape to the countryside when I needed peace and quiet. I’m always happy to go to my parents’, but I feel less of a need to do so now that I live here. Today, when I need tranquility to concentrate on certain things, I know I’m in the right place to do it.

Is that why you wanted it high above the city?

I can’t say that Pablo and I set out to be this high. It turns out that, in the end, I’m very happy with the overall effect, being so high up and not being able to see the street. I can only see it if I bend over, and it makes me feel cut off from the constant energy of the city. I feel a bit like I’m in a hot-air balloon.

You just mentioned traveling. Is it important for you to be anchored somewhere? You could have chosen to rent and not put so much effort into setting up your apartment.

It was a fairly pragmatic choice. As I have a permanent contract at the Opéra, everyone quickly advised me to buy rather than rent, telling me I should take advantage of it because of how Paris real estate is. I’ve rented lots of apartments, moving almost every year for five years, and then I bought my first apartment, which was 28 square meters in Réaumur-Sébastopol. Then Pablo and I bought this one. That’s when I felt like buying a fixerupper, because it was a two-person project, with the idea of making it our own utopia. I’ve never felt the need to lock myself up in my room, which is why the space is more open-plan.

As a dancer who’s also a model in his spare time, are you prone to dancing around the apartment, sashaying while doing the housework, or putting on little runway shows for your boyfriend?

Yes, we sometimes fool around and take photos for fun. But no more here than anywhere else and no more than anybody else would. When I have parties with my dance friends, it can quickly turn into trying on some pretty funny stuff we bought around Barbès. It can be fun, yes…

We have a dossier planned for this issue on children’s place in the city. Do you and Pablo ever think about making room for any?

(Pablo comes home, and Germain suggests he take part in the interview).

Absolutely, and we’ve already determined where we will be building their room. We’d just have to do a few small straightforward changes. We might have to split up the open part of the bedroom with a glass partition to maintain the airiness of the floorplan, with a curtain for nighttime. I’ve already thought of everything! It’s not an imminent project, but when it happens, because it will happen, we’ll know how to implement it. And to answer the question about children in the city, Pablo is Parisian. He was born in the 13th arrondissement, and his relationship with the city as a child differs from mine. A lot of parents say, “when I have kids, I’m going to move to the countryside or the suburbs to have more space” and so on. For us, it’s not a foregone conclusion. If we have children, they’ll live in Paris. I know Paris is expensive. But if we can afford it, I think a child has a rightful place in Paris.

Pablo: Yeah, I mean, we used to go to the park. I admit I’ve never really understood this debate. I can see the difference with Germain, who suffered from being all alone until he went to boarding school. In his village, he was the only kid…

Germain: In my hamlet, there were forty of us and no kids my age…

Pablo: …and he had to bike for half an hour to visit his closest friend. My best friend lived in my building; he was the neighbor downstairs, so in the morning, I’d see him and spend our days together.

Germain: From a socialization point of view, I think it’s more interesting to grow up in an environment with people around…

Is your tool – your body – starting to show signs of fatigue?

It’s already begun. I’m thirty now, and I’d say that since I turned twenty-five, I’ve been getting acquainted with the notion of wear and tear. I’ve got a bit of osteoarthritis in my foot, and I’ve got little blockages that I know will never really unlock. As you get older, you have to accept that certain things stay where they weren’t before. But there are also reversible things that improve with time. So you have to look at things with relative optimism.

Where do you see yourself postdance?

What I know for sure is that I’ll want to continue on in the live performance field, the art world. And I’ll have to see what shape that takes. Perhaps at some point, as I approach the end of my career, I’ll want to keep performing on stage as well. And I’ll have to find the means to do so without my body being a limit. Through theater, performance…

Is that why you moved in above the Cours Florent?

Exactly. That was the goal (laughs)! Living above the Cours Florent is quite funny because when you go home, you often walk by people screaming at each other, and they’re actually rehearsing their scenes. At first it was a bit confusing because we wanted to get involved. Sometimes, it’s also just people hanging around getting into real arguments, so it’s a lot of fun to ask yourself that question for two minutes. It all depends on how convincing they are (laughs)!

Photos : Charlotte Robin

Text : Jean Desportes