Kenny Dunkan, on his De Sede DS1025 Terrazza sofas by Ubald Klug.

You were born in Guadeloupe. Could you tell us about your childhood? How does one manage to dream of contemporary art while growing up on such a faraway island?

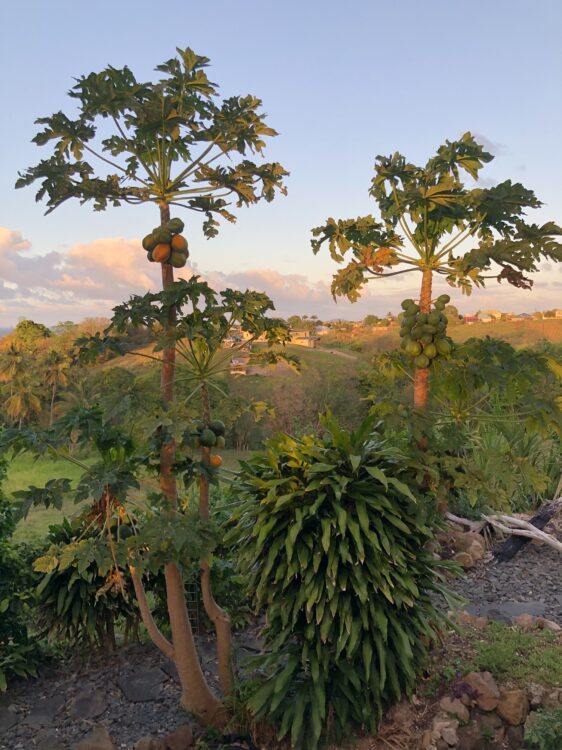

As a child, and even as a teenager, I never had dreams of contemporary art. The concept itself was quite fuzzy. We had no contemporary art museums or galleries, not even modern art ones. In downtown Pointe-à-Pitre, you can find small historical museums like the Schoelcher museum, and then again, few people even go to museums. There is a gap between people and art, but most of all, between people and history. Nevertheless, things happen here and there. The MACTe just opened its doors as the city’s first museum dedicated to the history of slavery, with an obvious focus on commemoration. There are some showrooms for contemporary artists and spaces for artistic residencies, but in the Caribbean, art is, I’d say, infused in life, through carnivals, rituals… When I was a kid, what I would dream about was beauty.

So you’d find beauty in different sensorial stimuli: the breathtaking Caribbean nature or the carnivals, for instance?

I’ve got my first aesthetic epiphany during a Mardi Gras parade, when I saw the Carnival Queen inside this pineapple-shaped carriage, wearing a shiny skin-tight jumpsuit with a black light that gave it a kind of supernatural aura. It was a mix of chants, dance, and sculptures – a total shock for eight-year old me. Beyond the aesthetical enlightenment, it was a bewitching sensorial experience. The music was filling the moist air with heavy bass. I think what I do as an artist today is attempting to record and transmit that sensation.

In your work, do you often invoke memories of the French Caribbean?

There are two kinds of carnivals. The first one is for the tourists: a sugarcoated fantasy of a carnival, all feathers and glitter, completely disconnected from the social reality of the French Antilles. The other carnival is closer to a social protest, with characters voicing their claims for social justice in the public space. These “Po” groups, like the mythical Akyio group from the 70s, play small drums covered in animal skins. They communicate a strong message about historical traumas, African historical figures, getting to grips with real life in the Caribbean, often with a tinge of irony.

Paradoxically, Carnivals are moments of truth. We use makeup to ultimately tell the naked truth, to turn artifice into reality.

You’re right. Carnivals subvert all the social codes, giving people the freedom to say anything they want.

Would you say that this liberating dimension of the carnival feeds your work beyond its formal artistic dimension, as it frees you to talk of who you are and where you’re from?

Sure, I use carnival as a magic potion, one that sets me free. During the carnival, you can be whoever you want to be, behind your mask. Among the French Caribbean “Po” groups, wearing masks is a very codified activity. When you put on a mask, it’s not a disguise. It’s an activation of a magic entity. You become that entity.

Then came the day when you moved to Paris. Can you tell me about your journey?

I dreamed a lot. Dreams are the foundation of my life. At night, I dreamed of beauty. As a kid, I was a quiet type, and I liked contemplating and analyzing things. I was always drawing, or doing other things with my hands. I watched the world move. Like many French Caribbeans, I dreamed of Paris. We feel bound to “Metropolitan” France, but this bond is very ambiguous. Historically, Guadeloupe is linked to continental France as a former colony. Political strategies were put in place to attract Caribbean populations to the continent, in order to repopulate the countryside. One example is the Bumidom, the overseas migration development bureau. This part of French Caribbean history was pretty traumatic for some families and for some children who moved to France. This bond stayed etched in our minds: move to Metropolitan France and find work. For me, it was the only place to go if I wanted to study art. Paris was the place where my dreams would come true. At the age of five or six, when I came to Paris for the first time, I had already told my parents that wanted to study in France. I didn’t know what exactly, but I’d already warned them.

In this regard, you told me about the Galeries Lafayette map…

Yes. At 17, my parents treated me to a trip to Paris before graduation so that I could visit museums and see the works of art in real life. I brought this Galeries Lafayette tourist map back, I circled all the schools I was applying to: Duperré, Estienne, Olivier de Serres, Boulle and I tucked it under my pillow. I was accepted at Boulle and Olivier de Serres, and I finally chose Olivier de Serres.

So you slept with the Galeries Lafayette’s map under your pillow, and then eventually were a part of the opening exhibition for Lafayette Anticipations, which is the department store’s Contemporary Art Foundation.

I think you can dream things into being, like a perpetual projection. A small part of your dreams will always come to life. And sometimes, reality can even exceed expectations.

There is a video, UDRIVINMECRAZ, where you are dancing in front of the Eiffel Tower wearing a costume made of hundreds of mini Eiffel towers, the same that are sold on the sly by people who are often black Africans. By the way, the City of Paris added your piece to its contemporary art collection. What does this video say about your relationship to Paris?

As the title suggests, this video depicts Paris as an obsession. On one hand, it’s a beautiful and a positive place where I was able to come into myself as an artist. On the other hand, it’s a city of disillusion, a violent place full of cruel destinies like those of the street vendors trying to make a living by selling souvenirs to tourists at the Trocadéro. I instantly felt a kind of bond between us. They too dream that Paris can set them free and bring them and their families a better life; they too come from former colonies. With this dance in front of the Eiffel Tower, I tried to materialize the bond between Africa and the Caribbean, but also my inner torments. I combine Guadeloupean traditional dances like the gwoka with Jamaican dancehall, and I dance myself to exhaustion. In the end, I literally collapse on the ground, it’s quite ambivalent and very strange. Some of the tourists look stunned while others show total indifference. When I got to the parvis with my suitcase and my jacket bulging out, some of the vendors tipped me off: “be careful, we can see your merch”. I was already one of them. In the beginning, I was afraid that I was trespassing on their turf, but I needed to activate this sculpture.

So how long have you been in Paris?

18 years now. Soon, it will be a half of my life. It wasn’t easy at the beginning. I can see it now. But it all went really well. I made a lot of friends at Olivier de Serres, it was a good place for integration. Then everything moved very quickly. I adopted this city, in a quest for new sensations, and ultimately took root in it. There were nights out and beautiful people. I don’t know how long I’ll stay, but Paris definitely made the person I am today.

Don’t you think that Paris produces this non-existing French fantasy? It sucks in lots of people from different French regions but ultimately expels many of them.

It crushes people, for sure. It’s a violent city: social divisions, smells, the subway – something I still can’t get used to – sounds, people that stare at you, people that don’t even look your way. You have to find your place and then never stop fighting for it. In art schools, I’ve seen what competition between students can look like, it’s staggering! (Laughs.) This city builds egos and then tears them down. It’s either a hit or a miss. You need to have a certain kind of character and accept its flaws. I also think that to love it one has to leave it. I often go back to the Antilles; I lived in Zurich, in Rome. These places felt like vacation. I missed the big city. I always miss Paris. Actually, what I really miss is people you can meet in Paris. When I came to Paris as a student, I met a lot of people. People I would’ve never met in the Caribbean. My new friends were Mexicans, Swedish, Hungarian, Korean, Japanese. It’s an Alpha city, but it’s not a melting pot. That’s where its complexity lies.

You talked about Rome. For one year, you were a fellow of the Villa Medici French Academy in Rome.

It was my first residency and my first workshop. That’s where everything began, I would say, where I developed my artistic vocabulary by experimenting in the workshop, in the gardens, and everywhere else within the walls of the Villa. At first, I hated Rome. I was feeling like a prisoner in this fortress on the Pincian Hill, next door to a bourgeois neighborhood, overlooking the city from a distance. When I finally went into the city, everything seemed so sleek – only tourists on Piazza di Spagna – it felt depressing. It wasn’t easy to find my feet at Villa Medici. It’s a big institution, I felt a lot of pressure. But I reminded myself that they chose me. It took me four months to warm up to it, when I started to meet actual Romans. It was like in La Grande Belezza. It really exists. To me, Rome is even more decadent than Paris in its excess. The chaos of it, the different layers of beauty, the climate, the gestures… It’s a Caribbean city! It’s the most Caribbean city I’ve ever been in. Its relationship to family, to food, its moving ground, its terrific thunderstorms.

There is a “fashion” aspect to your work. It’s neat and carefully done, and therefore pretty straightforward. As fashion campaigns do, your work mixes shock value, visual literacy and immediacy.

My work does have this “Applied Arts” dimension. At art school, we were taught communication. At Olivier de Serres, for instance, I studied visual merchandising and all these visual communication “tricks”. I translate the complexity of Caribbean culture through Western lens. I wanted to become a fashion stylist when I was a child. Later, I wanted to be a designer. Today I feel very close to fashion. When I came to Paris, I deciphered local dress codes, and I totally changed my look. I quickly grasped that people would react differently to you according to your appearance. Playing dress up felt natural to me. It was not only a game but also a tool, and my distinctive look often protected me. Today, I’m totally at peace with myself, I accept myself completely, so I have nothing to hide. Back then, I was going through a heavy transformational phase. I changed my hair style every day, I tried different colors, I played around with androgyny. I know exactly how people react to a hoodie-and-sneakers style. If I’m wearing something more dandylike, it’ll change. It’s as simple as that. I love dissecting fashion and all its concepts and connotations. It’s so playful. And I love juggling.

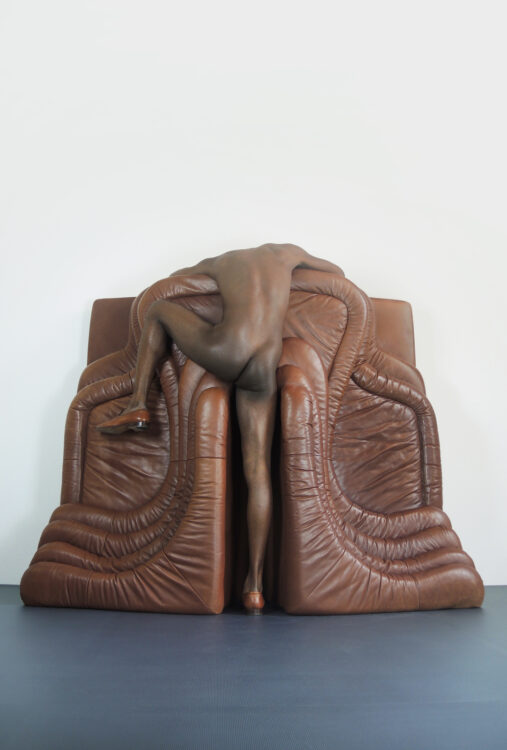

You also have a design approach. I’m thinking of your piece Affinities Are Miracles (2019) for instance, where a body is intertwined with an iconic leather sofa, the De Sede DS-1025 Terrazza by Ubald Klug.

There’s a form of absolute fetishization. I play with my body – my black body – which is objectified, fantasized, given many assignations, and my work is a way to be who I want to be: a dominant and dominated body, both sensual and sexual, welcoming and repulsing. It’s a way of playing around with iconic design objects, and with bodies which were commercialized during slavery, turning them into material goods as well. It’s a way of making connections between history, capitalism, and aesthetics.

Is our society irrevocably materialistic by dint of us being bodies?

There’s this obsession around objects, materiality, wanting to unveil all of that. But the spiritual approach is all-encompassing. A lot of my work evokes rituals, bursts, life, and more occult references. I think I’m making connections between different worlds. The relationship to nature – more so linked to the respect of nature being a living force that bears fearing. I believe in the power of nature, the healing power of nature. In the Antilles, we take “bains de feuillages” – baths infused with plants – to start the year on a high note. We also take midnight baths on New Year’s to regenerate and ward off evil spirits – we call them “bains démarrés”. It seems very natural to me. Everybody does it before partying. I had asthma as a child so I was forced to drink a bowl of milk in which an anolis [a small lizard] had been soaking. I haven’t been sick ever since. I was raised in a magical and spiritual environment, syncretic with Catholicism mixed with the beliefs of African slaves who brought along their dances, chants, cooking and outlook. The natives were already there, with their own strong beliefs. It all gels into an ultra-complex amalgam that can seem opaque from the outside, but is completely normal. Objects are a reflection of this. I’m French Caribbean, but I’m also French, and also European. I’m complex by nature.

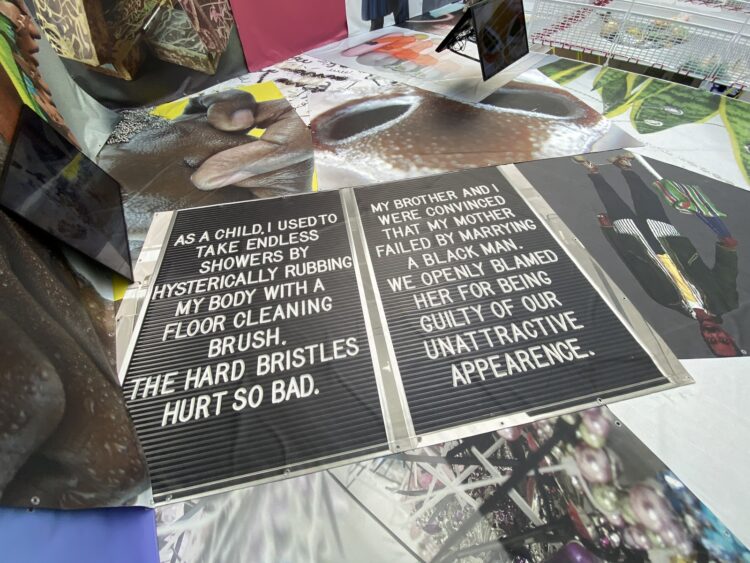

To quote you, “I had even convinced myself, when I was younger, that if I took never-ending showers while scrubbing myself with brushes, my skin would lighten.”

I discovered I was black when I arrived in Paris. In the Caribbean, everybody has the same skin tone, give or take. When you arrive in Paris, you realize you’re different, and this is made very clear. Some lighthearted jokes and some more systemic remarks, clichés I didn’t really pay attention to at the beginning. In the Caribbean, we strongly identify as French, we feel much more aligned with the mainland than with Africa. It stems from a rejection of our roots, we want to believe we’re more evolved, less rudimentary. The funny thing is that in the Antilles, everybody is mixed. I have European, South Indian and African origins. If you have a look at my family tree, you’ll find every eye color, every hair texture. It’s fairly strange being assigned – pleasingly, of course [laughs] – to one human category because of a specific trait showing up in our genotype. I’m often asked where I’m from, mostly by black people. I tell them to take a guess – they’re never right. Because of my slender figure, my dark skin and my fairly fine features, people believe I’m Fulani, a people from Senegal. Or when I was wearing a hat, covering my hair with my mustache on display, I was greeted by the Pakistanis that saw me passing by on my bike in Zurich, as if I was a part of their community. Even amongst people of color, it’s ambiguous. Ambiguity is everywhere.

On one of your pieces you wrote: “My brother and I were convinced my mother had failed by marrying a black man. We openly condemned her, holding her accountable for our unsightly appearance.” You blamed your mother for not marrying a white person because you would have deemed being mixed more acceptable?

Hearing this is always really brutal. This is the aftermath of colonialism, still lingering in the bodies and minds. At the time, there was a caste system with the mulattos, a term relating to animal cross-breeding. There was a classification of race mixing, with the quadroons for instance, and the lighter the skin, the higher the position was in society. This created an expression we still use when a baby is born: “Oh! Wow, he has a beautiful chappée skin.” Meaning a beautiful light skin that escaped its destiny. There’s also the word “chabin” or “chabine” that refers to light-skinned people, often with green or blue eyes. That’s the ultimate beauty standard, to which I look nothing alike, so I had many complexes. And my whole life, I felt like I was outside of my body, that this body couldn’t be mine. Because my skin wasn’t light enough, because my hair wasn’t straight enough, because my nose wasn’t thin enough. And I fantasized about a body I didn’t have, which caused me to be constantly looking in from the outside. It was an obsession, to the point where I blamed my skin color on my mother.

Can we discern the vestiges of slavery in your work? Maybe in your recurring use of chains?

Everybody can enjoy chains! [laughs] But some elements I find in hardware stores are definitely strongly linked to objects of domination and oppression that were used during the period of slavery, and I buy them in full awareness of this to master them in my own way and symbolically thwart history. But they’re also references to S&M, I create confusion between pleasure and pain. In my art, everything is concealed. It’s the case in this video I call Christophine. It’s a vegetable that became a traditional dish, the name refers to Christopher Columbus, who introduced it. But, as is the case for many things, no one questions its origin. In the video, I zoom in on this vegetable I’m caressing because it has spikes bending and perking up under my finger, it’s very organic and very strange. You can read a lot into it. But the colonialist approach is implicit. I have this piece where I press the mouth of a black dummy, the kind used to practice mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. I made a tone-on-tone background where everything is very shiny, very appealing, kind of like chocolate. I called it La Pièce chocolat. It’s about the history of chocolate, which is a product that creates joy, the joy of consumption, but also a product that caused suffering on many bodies. You can apply pressure to things and get a kick out of it. When I find something particularly cute or even beautiful, I love squeezing it, causing suffering to what brings me joy. These references are always implicitly present in my work, either through sexuality or humor, so that it remains lighthearted. I work in layers, and the deeper you go the sharper and more incisive they get.

In your pieces, underneath their seductively playful, meticulous aspect, there’s a form of harshness.

They’re traps.

How did you acquire this particular language, this assembly of hose clamps, pendants, calabashes, pearls, and nuts?

I developed all this plastic vocabulary at the Villa Medici. And also during my studies at Arts Déco. I was aware I was experimenting with my vocabulary, and that my sculptures weren’t complete, but that I would re-exploit all these forms and all my areas of research. My sculptures are independent, but I associate them with narrative systems to complexify them.

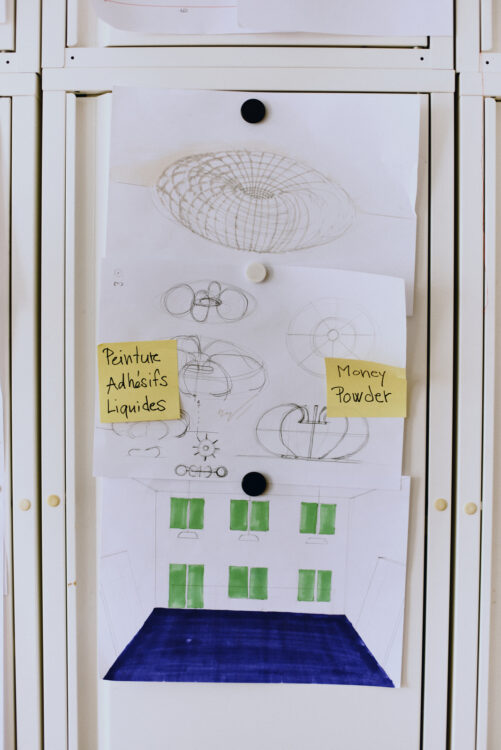

Now you work from home. We’re in an extremely curated apartment, almost like a design gallery. In a room at the end of the enfilade of the reception, we stumble upon your workshop with plans all over the walls and materials everywhere. It’s a world-withina-world, the facade and the back of the shop, the display and the sanctuary…

Yes, not everyone can enter the workshop. But the apartment also remains a private bubble only the people closest to me can access. Despite its dramatic flair. I don’t host much in it. It’s a very intimate space. I don’t throw many parties here, I prefer going out! Some artists are opposed to this mundane aspect. I’m used to it because of the fashion sphere I was a part of when I was around 20 years old. Being a model made me less shy, it made me proud of my body I had hated for so long. In all my apartments, I’ve always painted the floor white without notifying the landlord. When the place was semi-furnished, I’d put it all in the basement, I even threw some furniture away, I sacrificed it. I’d rather have lost my deposit than lived with stuff that didn’t match my taste. I always need to be in control of what surrounds me and create interesting compositions using different textures, things that bring me joy, like plants. They’re actually in charge here. If I put them in a spot that doesn’t suit them, I need to relocate them and it takes time. My plants teach me how to let loose a little. I can’t help always needing to be in control.

In your bedroom, your wardrobe is out in the open, perfectly displayed on huge racks. Is this another installation?

My clothes are on display because it was a part of my first exhibition at the gallery Les Filles du Calvaire. I confined my whole wardrobe under glass for three months. I’d only kept a few utilitarian clothes. It was a way of showing how we can let go of our possessions and live without anything superfluous, an experience of bareness. It was a bit unsettling at first, but I discovered how cool it is not having too many choices! The passerby saw my most intimate belongings. It felt weird hearing people commenting on my wardrobe pieces sometimes. I stood next to them and listened. It was as if they were talking about someone who had died. It made me think about the things we leave behind once we’re gone. I was once again outside of my own body.

You collect many design pieces from the 20th century…

I encountered design in a hardware store in Guadeloupe when I was 11. At the checkout there were all these décor magazines. I saw the cover of AD with a new Philippe Starck hotel. I was shocked. I asked my mother to buy me the magazine. I realized that design is something very playful, with particular names for objects: the Coconut Chair, the Marshmallow… That’s how I started educating myself: I keep in mind a catalog of icons I want to experiment with. I’ve often bought second-hand design pieces online for next to nothing, to live with them before reselling them. My relationship with objects is visceral, particularly with the ones radiating a magical aura. I’m thinking of Sottsass’ approach, with its totemic dimension evoking rituals. His creations are definitely not neutral objects. I was drawn to the De Sede sofa for its sensual and organic aspect. To me, every object is an extension of the body: they grant us magical powers.

Why did you choose such a Parisian apartment?

It’s temporary. When I finally own an apartment, I don’t think it will adhere to these codes. It will be sleeker, with raw materials, evoking a kind of dissonance. Everything you shouldn’t do in interior architecture, every material you shouldn’t use, I think that’s what I’ll use [laughs]. It will be somewhat experimental, similar to when I conceive my sculptures with collages, unexpected combinations of objects, materials…

Your first solo show, Keep Going!, at Les Filles du Calvaire gallery, was an almost immersive exhibition, in the way you welcomed the viewer into your mental universe. Having it in 2021, in the midst of the pandemic, was also not the most auspicious premise!

It was really great. It created intimate moments, which led to very interesting meetings in the art world, when these people had time on their hands because there weren’t as many shows on at the time. They were in my body, in my head, and that’s what I enjoy most about what I do, meeting people, but intimately. I can speak in public, but it takes some effort.

What are you working on at the moment?

My next project will revolve around performance and video. I’m going to Guadeloupe to shoot a video. It will be about my vision of my island, of this ultra intriguing, particular nature that can be frightening, sometimes toxic but is also nourishing and protective. And I’ll make some… revelations. That’s for the beginning of 2024. And then I’ll do a solo show in Frankfurt, my first-ever exhibition in Germany.

You’re a sculptor, but also a videographer, a designer…

That’s what being Creole is all about. Being many things at once. Unexpected encounters between cultures, objects, flavors. To me, it feels very natural being many things at once, everything at once. The “Tout Monde” defined by Édouard Glissant. That’s the Caribbeans, being a fragmented being, ambivalent, contradictory, and still exist. We can be both fragmented and happy. In every fragment we can find reassurance or interrogations and navigate the in-between, as if they were islets filled with luxuriant nature.

Photos : Charlotte Robin

Text : Jean Desportes