Home Page » Reports » In conversation with artist, diarist, researcher Benny Nemer

In conversation with artist, diarist, researcher Benny Nemer

North Pole Lights

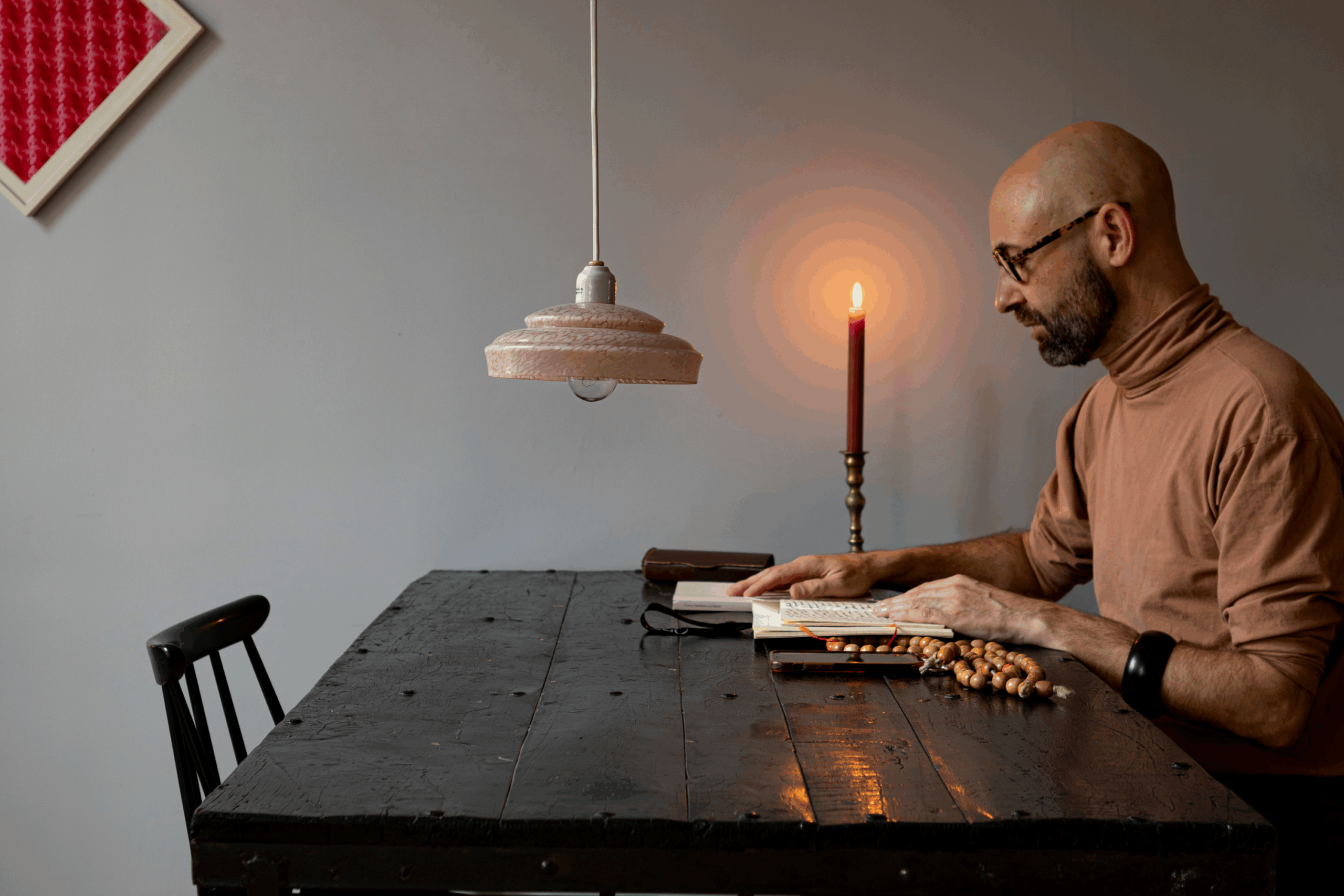

In his Parisian home, located on Rue du Pôle Nord, Canadian artist Benny Nemer is reinventing the tradition of artistic and intellectual salons that emerged in the 18th century. Through these gatherings, he showcases a contemporary art of living in a handful of rooms.

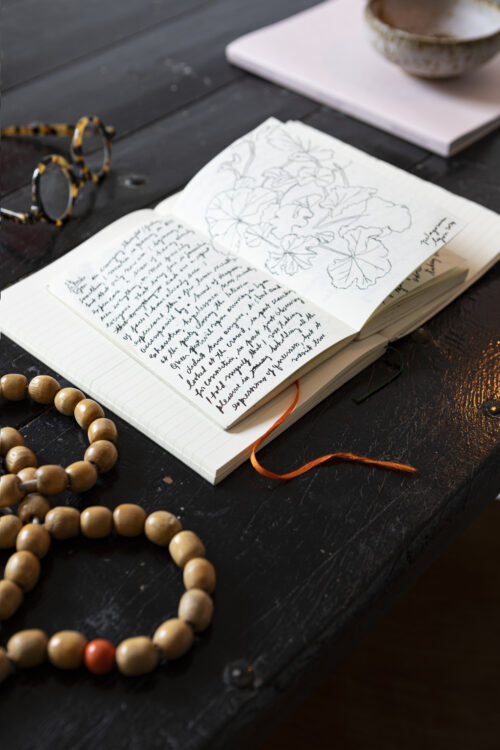

It was through one of the "Salons du Pôle Nord" that I discovered Benny Nemer's apartment. I was somewhat familiar with this Canadian artist's work, the way he uses epistolary exchanges, how his handwriting spreads across his exhibitions, but I didn't know where he lived. Teaching in Ghent, he moved into this Parisian apartment in 2021, as one decides to settle down for an indefinite period. For an artist who had completed numerous residencies, for varying lengths of time but always predefined, it was the beginning of a new chapter. The "Salons du Pôle Nord" were an opportunity to bring friends together, and as they came with others, to meet new people, but even more than that... I received his invitation without knowing that each event was carefully organized and, so to speak, the subject of a performance, an artistic gesture. On Saint Sebastian's Day, guests were asked to come and decorate vases with flowers that represented the wounds of the martyr as depicted in classical painting.

These artistic rituals, far from being gratuitous, unite a queer community around symbols. Benny Nemer, who has explored cruising spaces and libraries as places of intimate memory for LGBTQ+ people in his work, has increasingly invested in domestic spaces or sought to transpose them into exhibition spaces. This involves repainting a wall, seating visitors, and inviting them to correspond with each other. The artist unfolds narratives through gestures and protocols that are like personal addresses.

To mark the entrance to his apartment, he hung a rose above the peephole. For those who know him a little, this simple gesture speaks volumes. The host's thoughtfulness and consideration make the walls seem to recede, and it is difficult to judge the actual size of his apartment. The lights move, as does the furniture, and it is just as easy to arrange them for a sit-down dinner as it is to spread them out to accommodate thirty people for a birthday party.

In fact, only the bathtub in the bathroom and the kitchen itself remain stationary, indicating the apartment's vital functions. Everything is lived in, but in such a unique way that it almost makes you feel out of place in the way you think you live. There are no plastic cups or disposable dishes at Benny's, and everything you hold in your hand or put in your mouth has been crafted and chosen. The bubbles in the glass and the chips on the plate have something rough, charming, and unique about them. No detail is left to chance, or rather, nothing is left to chance, but not out of simple aesthetic concern, but rather out of an almost ethical quest. The art of living, because it requires both self-knowledge and the development of taste as well as the putting of principles into action, is perhaps the only true art form.

What’s the first thing you do when you arrive in a space that makes you feel at home?

That is a tough one to answer, because I admit my sensitivity to my surroundings sometimes prompts me to change various elements. I am especially intolerant of bad lighting, I almost feel physically unwell when subjected to harsh light, so this is often the first aspect of a space into which I intervene. I feel quite aligned with Jun’ichirō Tanizaki’s ideas about light and darkness in interior spaces in his iconic 1933 book In Praise of Shadows. But I also recently saw a meme circulating on social media, a video of a dimly-lit apartment and a voice saying, “I can tell you are gay because none of your overhead lights are on. I know when I am in a gay person’s house when I cannot see shit.” I love the idea that my sensitivity to lighting is part of my queer sensibility.

You’ve moved around a lot in your life, and the lack of furniture reflects this habit of trying to have as few objects as possible, but their age nevertheless helps to create a sense of stability, and everything seems to have been chosen, including the materials. It’s clear that you’ve settled in over time. How have you furnished your home?

In the adult chapters of my life, I have created homes for myself in Toronto, Montréal, Berlin, Edinburgh, and Paris. I have also participated in numerous long-term artist residencies, especially in Stockholm, Brooklyn, Paris, and Innsbruck that felt more like living than simply visiting. These many moves have required me to repeatedly go through all of my worldly possessions and to decide what truly matters to me, what I really wish to have follow me as I embark on a new experience of living. I would like to believe that I have learned to let go of many things and that I now have a rather lean body of possessions. But I love objects, I attach meaning, memory, and emotion to them. The result is a carefully curated ensemble of furniture, garments, objects, books, artworks, and paper ephemera that remain in my life. Each object has a story, often a rather special and elaborate one. I became attached to a fauteuil upholstered in pink velvet in my temporary studio in Stockholm, for example; it accompanied me through a painful amorous breakup. Three Swedish friends took it upon themselves to transport the chair as checked luggage on their flight when they came to visit me in Edinburgh; we transported it on the bus from the airport to my apartment! So there is no way I will ever separate from such a storied piece of furniture, so enveloped in my relational biography. Quite a few pieces belonged to my grandmother, Rosalie Namer, who collected Québécois peasant furniture from the 19th century. All of it is made of pine, a bit of the Canadian forests here with me in Paris.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen plastic, and the metal is never polished or gleaming. There’s a search for softness in the materials and colors, and in the end each object seems manufactured rather than mass-produced. Even your glassware shows bubbles that indicate recycled or hand-blown glass. How conscious is this research?

This also seems to me the influence of my grandmother, who greatly valued the skill and craftsmanship of artisans. Her aesthetics as a potter were highly influenced by Japanese ceramics, which led among other things to a deeply wabi-sabi sensibility that was transmitted to me. So unpolished bronze candlesticks, underlit rooms, asymmetrical arrangements all feel quite natural to me. Living with my grandmother’s pottery also makes me sensitive to the power and beauty of seeing and even feeling the traces of an artisan’s touch. I am always attracted to things that carry such physical traces.

In Japan, there’s a word for objects that acquire a soul after a hundred years. It’s clear even from your kitchen tools that you’re attached to old objects, and that this goes beyond aesthetics… You talk about wabi-sabi, would you say it’s a philosophy of life?

I wonder if it really takes one hundred years for an object to acquire a soul. I think of Jane Bennett’s ideas about the vibrancy of matter, which she extends to all objects: old and new, natural and synthetic, acknowledging the “thing-power” embodied by everything from an antique vase to a broken plastic fork. Bennett definitely critiques the culture of creating single-use, disposable objects as a denial of the vitality of matter, but I sense that in her worldview, even mass-produced junk has vibrancy.

I do have a fondness for old things, used things, things that carry histories, including histories unknown or opaque to me. I buy a lot of second-hand clothing and prefer to go in search of kitchen utensils at a brocante rather than at BHV (a famous department store). But I sense I am more attracted to the uniqueness of an object than its oldness; an object has to have something special about it, and some possibility of entering into dialogue with other objects in my home. This seems more important than the object’s age, although things from different eras often possess unusual characteristics that appeal more immediately to me. This might include wabi-sabi qualities, but not exclusively. I do, however, feel totally transported when I enter a space that is governed by wabi-sabi principles, like Le sentiment des choses, a gallery in the Marais that I adore.

Ceramics are an important part of your life and your work, and I’d like to talk to you about those of your grandmother. You use them on a daily basis, but you also collect them and make them the subject of your work: a living museum. Performances to perpetuate the memory. Can you talk about this heritage in the present?

I am the grandchild of Montréal potter Rosalie Namer (1925-2006), whose influence on my life cannot be overstated. Among other things, her artistic kinship instilled in me an early aesthetic sensibility, a practice of epistolary writing, and a sympathy with flowers. When she died, I inherited some three hundred pieces of her pottery, which now fill my kitchen and guide the stylistic orientation of my entire home. Rosalie exclusively made pottery for everyday use, she produced few purely decorative pieces, so her pots are—and have always been—part of my quotidian aesthetic and haptic experience. Initially, my adult artistic practice had few similarities to Rosalie’s: I began as a video and performance artist, creating chiefly conceptual works. But some years ago, my practice expanded to include more material gestures involving flowers, letters, and vases, bringing me in closer proximity to Rosalie’s artistic universe. I started creating still life arrangements using her pottery and works that activate our postcard correspondence from the 1990s. More recently, I embarked on a project entitled Musée Rosalie Namer with my collaborator and friend August Klintberg. The project activates Rosalie’s legacy through a series of artistic gestures involving dancers, art historians, and florists. We recently produced a video installation in which, together with dancer Stephen Thompson, sixty pieces of Rosalie’s pottery are handled, arranged, and rearranged.

In your work, vases and bookcases are staged, summoned as receptacles around which people can gather. A list of books to share and a floral gesture are addresses that you make to the public in exhibition spaces. What is it like for you?

My doctoral studies were concerned with the libraries, domestic spaces, and gardens of a four elder gay scholars who let me spend long periods of time in their homes in Amsterdam, London, and Montréal. These research visits brought about significant changes in both my artistic orientations and my way of inhabiting domestic space, sharpening my interest in the ways books, epistolary material, botanical matter, and other objects co-exist in a home. These concerns are now quite central to my artistic practice. It is true what you say that now, almost everything I exhibit has some rapport with the intimate sphere of the home, especially the way I work with floral arrangements and postcards, like stylized glissements from quotidian acts of sending letters and offering flowers into the exhibition space. The scale is kept intimate rather than creating monumental botanical installations or big text works. I tend to prefer videos to be on screens rather than projections, and audio through headphones rather than speakers.

Your bookshelf is an aesthetic object in itself, with books listed according to their color; in other words, when you’re looking for a book you’ve read, do you remember what you were reading? How did you come up with this classification?

Organizing my books by color is a purely aesthetic project. I have never liked the visual chaos produced by arranging books alphabetically. Naturally this is a more practical system, but it seems to ignore the book’s aesthetic and material properties. I have always arranged books by color, although this approach has felt particularly important in fostering a feeling of visual harmony within the limited space of this apartment. My books are kept in a room that also serves as a wardrobe, a salon, my work area, dining room, and my bedroom. So it is important to keep the overall feeling of this room calm, uncluttered, balanced. Blocks of uniform color help to achieve that. I once believed that I knew the color of each of my books, so that finding books by color wasn’t a challenge, but over time this theory has been proven foolhardy; I often need quite a long time to seek out a book, especially those whose covers are somewhere between white, off-white, cream, and beige. On more than one occasion, I have simply given up my search!

Speaking of color, the walls of your flat are a combination of ochre and sanguine. There’s a warmth that comes from this arrangement that doesn’t try to make your flat seem bigger. How did you arrive at these shades?

I have a rather strong orientation towards certain pale, warm grays. It is a fascination that expresses itself not only in my home but also in artworks. I often ask galleries to paint the walls gray or “greige” for my exhibitions. I brought this sensibility with me to this apartment, wanting to model it after the moody Danish interiors in Vilhelm Hammershøi paintings, so I painted the walls and two armoires the same gray. But shortly after moving in, I encountered a sanguine drawing by the artist Cyril Duret, a scene of a figure standing among trees and bushes, their body merging with the vegetation through deft, meticulous hatchmarks. I bought the drawing in a rare coup-de-foudre moment, and hung it in the cinder world of my gray main room. The red of Duret’s sanguine began to pulse into the space, sending out its hot signal in a gentle but somehow demanding way. It was so powerful that it brought about a redwards shift to the décor: I found myself adding other red details to the room: a sang de boeuf amphora and dark red candles, but eventually I had the gray sofa reupholstered in a sanguine velvet, bought reddish blinds for the windows, rust-colored bed linens and pillows. I hung a Cy Twombly exhibition poster scrawled with red letter forms on the wall. Red is also dominant in the kitchen, in this case taking a cue from the terra cotta floor tiles.

You have lots of vases that you use for different flowers and arrangements. How do you choose flowers for your flat? Depending on your mood and the season? In your ritualized way of living, one senses a Japanese influence…

It would be challenging to summarize my personal relationship to flowers and how I live with them, for it a great, many-chaptered love story that began in childhood. My domestic life with flowers is guided by both aesthetic and affective impulses and, since moving to Paris, with the friendships I have established with a few favorite florists. Sometimes I simply pick something for myself at a neighborhood flower shop, but often I prefer to enter into conversation with a florist, to compose something together through conversation. I love transporting the final bouquet through the city.

My vase collection—which began with eight vases from within the collection of pottery I inherited from grandmother—is quite vast and diverse. I now have about eighty-five vases in glass, marble, brass, wood, and ceramic: gifts and flea market finds, antiques and a few precious pieces made by ceramicist friends from France, Belgium, and Sweden. And while this collection enables all sorts of floral possibilities, there are still moments when I receive flowers and cannot find the right vase to hold them. But I have grown to love vases even without flowers, I am fond of and fascinated by this particular kind of vessel, its history and cultural meanings. I like that an empty vase can suggest flowers without actually holding any. My artistic and intellectual activities are increasingly oriented towards vases, and I have had the chance to produce a few series of vases in collaboration with potters for some recent artworks.

It’s important in your work, which is ultimately very relational, to receive people. You regularly host salons: what do you mean by this and how do you see this age-old practice that you’re renewing?

I began hosting salons during my doctoral studies in Edinburgh. I was quite lonely in that city and found it difficult to create the community I needed. So I tried to generate the social and relational culture I craved by initiating salon events and inviting literally everyone I knew to my home. I asked friends and colleagues to enact miniature performative gestures throughout the evening—a florist arranged a bouquet, a writer read a single poem, a drag queen applied lipstick to every guest—as a kind of cultural programme, distinguishing it as a salon rather than simply a house party. Interestingly, many of my Edinburgh guests told me that my salons filled a void in their own social lives, and most became dedicated salon attendees. I called the event Salon Rose, which felt aspirational and gently queer.

I moved into my Paris apartment on the rue du Pôle Nord in 2021, shortly after the pandemic and une rupture amoureuse dramatically reorganised my social networks in this city. I felt a not-unsimilar frustration with my social life, a need for connection and community that I could not seem to access. So I reinitiated my salons, this time as Salon du Pôle Nord, as a way of fostering the social culture I wished to be part of. Because of the size of my apartment, the guest list was a bit more limited, more curated, never more than 25 people at once. I shifted the cultural programme of these salons to be more collective and participatory: I asked every guest to bring a single flower, for example, to contribute to a large collective bouquet or to affix in a herbarium. The salons have become joyful spaces of encounter, exchange, and floral pleasure. I’m so glad I invited you to one of these salons, now almost two years ago, it was in fact at this salon that we met in person for the first time!