Rosa Maria Unda Souki, artist.

The first thing that strikes you as you enter the apartment is the sky. The yellow blinds have something solar about them – even though the choice of color came built-in, as a means of identifying each of the buildings in the Marcel Lods urban planning project. Those modernist building blocks, which remain modest in height, are structured around various squares, to give each apartment an unobstructed view – and the sense of space and tranquility provided by the trees and ponds is not contradicted by the chatter of neighbors. A sort of city within a city, this peaceful neighborhood alleviates any impression of density. Rosa Maria quickly converted the balcony into an extension of the interior, to create an echo of the patio around which her childhood home in Mexico was laid out. There, she can have breakfast with her feet in the grass – or rather, Astroturf – have an evening tipple under the string of lights, and devour a good book al fresco. On either side of the bay window, plants take pride of place; those that have been moved several times and can finally put down roots, as well as those bought more recently for their scents and colors. A part of the “forest,” as her daughter who dreams of living among magnolias calls it. In this compact apartment, where the easel is next to the dining table and the desk not far from the sofa, it’s the objects that define each space. Bright colors, such as the red of the sideboard’s compartments or the blue of the tablecloth and chairs, give a sort of joyful rhythm to the room.

From one house to the next, you’ve represented your living quarters on numerous occasions, sometimes with a few recurrences. A few objects seem to be following you on your journey. Can you introduce these markers of home to us?

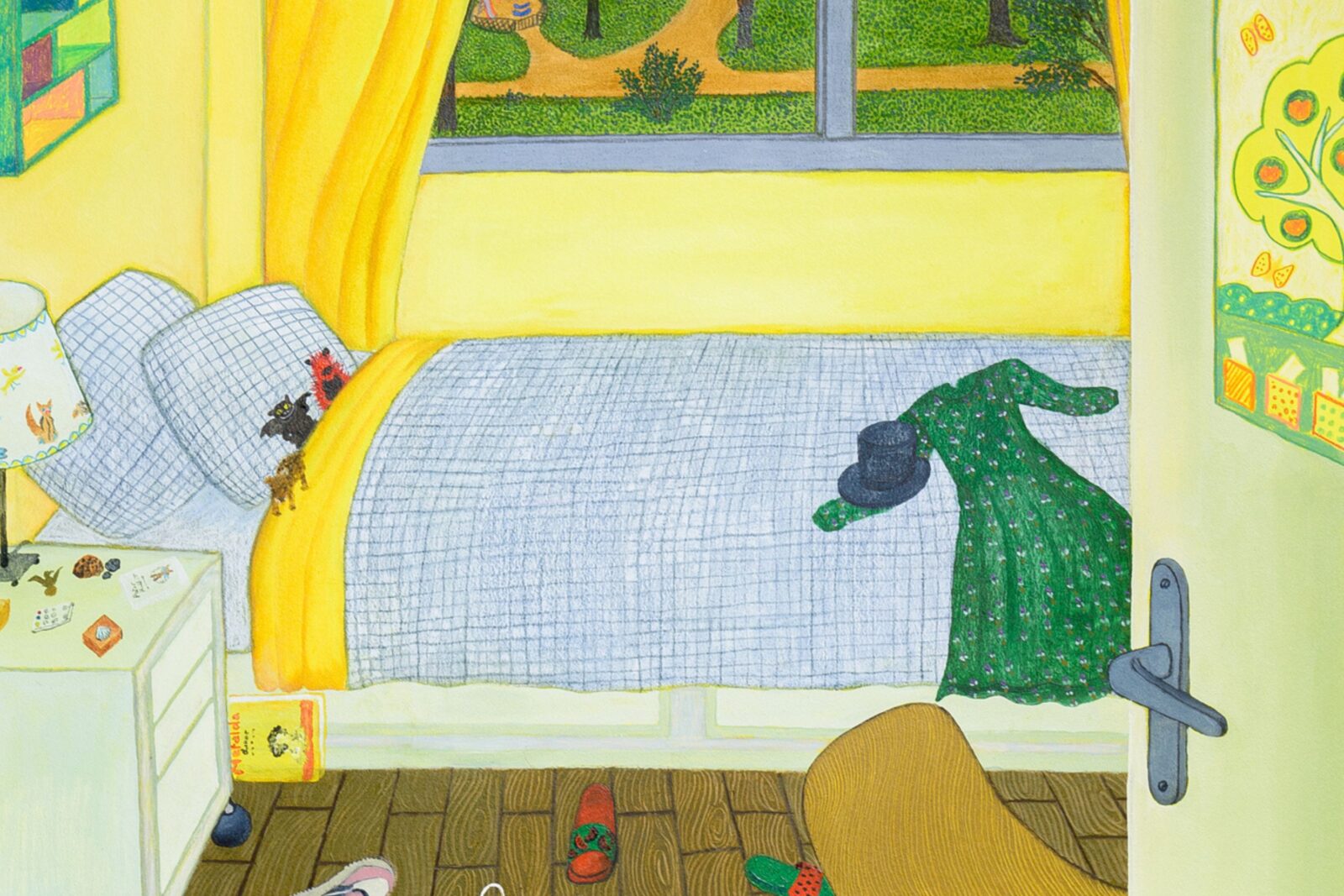

I’ve moved so many times that I’ve had to learn to travel light, or at least to choose what I’m going to surround myself with. There are items that you can easily replace, like certain books, and those that you can buy as you need them. Furniture is bulky and, when I first moved here, I quickly found the essentials through the classifieds. Making a home takes both time and a real personal, emotional investment. It can be as simple as a few adjustments, the way you lay out the space, furniture configurations, the objects you choose and where you place them, all of which takes on a particular meaning. When I came back to the Paris area in 2019, after almost ten years in Belo Horizonte, I was with my daughter and it was even more important to have reference points. She wanted Toto to come with us, and with this dog, there were also memories I didn’t want to deprive her of. So I took a painting from my childhood home in Guama, the family photo albums, a few knick-knacks, letters and books that are a part of me. There’s poetry, particularly Lorca’s, but also children’s books, which I have a passion for. I repurchased many of the ones that had impressed me when I was a child in London: stories that dealt unpretentiously with cultural difference, without omitting anything about the danger of racism, but also illustrated books that talked about building tree houses. I wanted my daughter, in turn, to be able to browse through them and, for example, share my amazement at Lothar Meggendorfer’s Grand Cirque International, a magnificent 1887 pop-up book that recreates the atmosphere of a circus, and then read her Venezuelan publisher Ekaré’s most recent titles.

Photographs: Fonds Lods. Académie d’architecture/Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine/Archives d’architecture contemporaine

Works: Grégory Copitet/Galerie Ariane C-Y

You mention a painting that was in your childhood home. What was your family’s appreciation of art?

My mother was a language teacher and my father was an architect who also trained as a landscape architect. He had an eye for art and, at the Central School of Architecture in Venezuela, he had met the German artist Gego, who had moved to the country post-Bauhaus. His collection was enriched by friends and local artists like Guevara Moreno and Armando Reverón. The painting I still have is by Victor Millan; it’s folksy in style and certainly influenced me a lot, as did the environment I grew up in. All these works were more than just objects, because there were always stories behind them. In a way, I’ve carried that torch.

With your works, your collection? There are some more recent paintings on the wall…

Yes, I have works by other artists, like Randolpho Lamonier, whom I met when I was living in Belo Horizonte and working at the School of Fine Arts, where we had set up a laboratory for around twenty students, including him, and I’ve been following his work ever since. Again, these are stories of continuing friendships. There are also paintings by Thomas Ivernel and Jacques Bibonne. It’s not just what they show but also what they represent that I keep on the wall, like the photo of my father that I still have to hang.

Photographs: Fonds Lods. Académie d’architecture/Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine/Archives d’architecture contemporaine

Images are very present in the environment in which you live and work. Some artists may feel overwhelmed by so many stimuli, but you feed off them, incorporate them into your work and make them grow.

When I got the keys to this apartment, I came here for a week just watching the light flow through the space, following it all day long, sitting in the empty rooms. I savored the happiness of having found a home, while thinking about how I was going to occupy it. I made lots of plans and drawings. The two would merge, and I’d plan my move and how I’d find things, with the memory of where I’d put them. I remember that the dolls were the first things I unpacked when I arrived at the Récollets convent in 2019. Objects allow me to make the connections between spaces; it’s my world that I unpack. It’s also true that images follow me: my father’s photo, but also my mother’s, my maternal grandparents’, pillars that I always put together on a wall.

Kind of like an altar?

We’ve just built a niche in my bedroom. A house is a permanent construction site, and with the arrival of my companion, we built new furniture, reorganized certain spaces like his office, but also the bedroom, and I was able to make myself an altar. In Latin America, we have a lot of altars for saints and the departed, but mine is a bit secular, with a miraculous Virgin Mary made by my aunt, figurines of Saint George, Saint Anthony and Oshun, the divinity of abundance in Brazil’s Candomblé culture, and a few other pieces of jewelry made by my daughter, as well as family photos. These objects and mementos that are close to my heart form a kind of protection.

From this altar, we move on to the notion of home, and in your drawings and paintings, there’s the same movement that seeks to grasp beyond the walls what makes up the heart of a house. You use numerous shortcuts, certain distortions of perspective. Is your work a kind of condensation, a miniaturization?

I often think of dollhouses, and in particular of some of the most meticulously detailed models. During a visit to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, I was fascinated by the reproduction of a miniature house commissioned by a very wealthy family from various craftsmen, not only to provide a plaything for their child, but also to have an object that was as faithful as possible to the luxury in which they lived. It was from this observation that an intuition came to me that was very important for the book Ce que Frida m’a donné. I wanted to show Frida Kahlo’s house at different periods in her history, and, in particular, as it appeared in her childhood – which is very different from today. There are a few archival photos and accounts by the household staff that provide more information. The house was built in a neoclassical style, closer to French architecture than to the predominant Spanish colonial architecture of the time. Frida’s father, as official photographer for Porfirio Díaz, had a very good situation before the revolution ruined him and his daughter’s medical situation led him to mortgage the house and sell the objects. It was Diego Rivera who bought the mortgage and turned it into what is now the Blue House. To find the look I was looking for, I left no stone unturned, and in the end, it was through the dollhouse, with the reproduction of the furniture that had once been there, that I was able to paint the first family pictures. It’s a way of holding on, preserving and cherishing.

Your book on Frida Kahlo, while highly researched and referenced, is nevertheless wary of the popular icon she has become. By focusing on her homes, you suggest an angle that is both specific and situated, approaching her from the point of view of your own interior and life experiences that may echo hers. You establish an intimate connection with her, which helps to restore the character’s fragility and make her experience emotions, but also exposes you a great deal. This is your first experience of writing, and paintings were the first part of your approach. How did this project develop?

This isn’t the first time that I’ve used a house and its surroundings to get closer to a historical, artistic figure. Back in 2010, I worked with the houses where Federico García Lorca was born, lived and died. Of course, I loved his poetry, just as I love Frida Kahlo’s painting, but this research work I was doing was a way of making an intimate connection with them. The knowledge I was acquiring enabled me to get to know myself better. I remember the day my mother came to see my work in progress on my way back from Valderrubio [the village where the García Lorca family home is located] and said: “wait a minute, I have to show you something,” and there she showed me the picture of a painting I’d given her of my childhood home in Guama. In fact, it was the same painting! Of course, the objects were different, but there were many similarities between them and, above all, it was the same angle, the same point of view that I had projected in Federico’s house and in my childhood home. For me, this work is a way of reinventing my universe, but at the same time, it’s a way of digging deeper into it, through this process of projection. What immediately interested me about Frida was not so much her portraits as her still lifes. Salomon Grimberg wrote a book about them, Frida Kahlo, the Still Lifes, which was a great help to me. It includes fruit as well as objects, ex-votos, dolls and text, dedications that convey something intimate in the painting. Bringing it back to me through text is both a way of adopting a point of view, of unpacking my research (which is not that of an academic,) of showing what there is between the paintings and all the connections I create; once again, it’s very autobiographical, it’s very much about my life.

You talk about the notion of the portrait, and while it’s true that you don’t use the human figure in your work, we can nonetheless talk about portraits in terms of objects and space.

The influence of architecture is undoubtedly crucial to my work. I’ve kept my first drawings since the Fine Arts School in Caracas in 1993-1994, and I’m always surprised to see how they already contained everything I was to develop afterwards. I was able to show them at the Cité Internationale des Arts, thanks to Anaël Pigeat, and they already featured houses with something theatrical about them. There’s a connection between all these places, and the objects that link them create a continuous interior space, which is my own. Even in the “La Recherche” series and in “Impossible chez nous”, all these apartments I visited but didn’t get for one reason or another (which I detail in the caption) are places in which I’ve projected myself, where I’ve considered living for a moment, with the violence and fatigue that follow when you realize it’s not going to be possible.

The narrative dimension is very much present in your “La Recherche” series, which is articulated in two stages with “Le chez nous possible” (Our possible home) and your move to this apartment at the Grandes Terres. I was surprised to see the white walls on the way in, whereas they sometimes appear yellow or bluish in your work.

I’d love to put some color on the walls, but let’s just say that’s a project for another time. I have a stable home, thanks to a lease in my name, but I’m also renting it. I wouldn’t dare put holes in the walls and, for example, everything you see hanging here is held up with adhesives. To come back to the colors, I paint not only according to what I see, but also according to what I perceive. There’s always an intuition behind it, connected to an object, a moment or a feeling. When I first arrived, I was struck by the hue of the sky, which I hadn’t seen before and which was reflected on the walls. The yellow light of dusk flooded in, and it was also a positive feeling that I tried to retranscribe. At another moment I’m representing, the fog came down on the square one morning and the walls were tinted blue, it was quite magical, the impression of another reality.

Photos : Fabienne Delafraye

Text : Henri Guette